BY: Ibrahim Hersi, Minnpost

Over the last several years, researchers and government officials from Europe and different parts of the U.S. have regularly visited the Twin Cities to learn about the East African Muslim community’s political and economic success.

“Minneapolis is viewed around the world, particularly in Scandinavian countries where the Somali diaspora is growing, as a model for Somali integration,” writes Stefanie Chambers, a political science professor at Trinity College, in her recently published book comparing the Somali-American communities in Minneapolis and Columbus, Ohio. “Other American mayors, such as the mayor of Portland, Oregon, have visited Minneapolis to learn about policies that can help their cities better address the needs of Somali immigrants.”

For all the talk of success and integration, however, the more common reality for Somali-Americans in Minnesota is more complicated, if less comforting. “From outside, the community seems to be doing really great,” said Ahmed Yusuf, a Minneapolis Public Schools teacher who’s written about Somalis in Minnesota. “But when you look deep down, we’re struggling big time, except for a few individuals who have risen above as the cream of the crop.”

The Story of a Success Story

The history of the Somali-Americans in Minnesota echoes that of many immigrant communities in the United States. When the first waves of Somalis arrived in Minnesota, in the early 1990s, many entered the workforce via unskilled jobs at meatpacking plants, where the work didn’t require prior work experience, advanced degrees or fluency in English.

But as the community grew, and as more Somali immigrants improved their English skills and earned career credentials, they branched out into more industries and professions — including work helping local and state government agencies bridge the cultural gap between service providers and the growing number of Somali clients in Minnesota.

They also started small businesses. Today, though Somali-Americans are in almost every sector of Minnesota’s workforce — and are particularly well-represented in the health, education and financial-services industries — perhaps their most conspicuous presence in Minnesota, especially in Minneapolis, to due to small businesses: the myriad restaurants, coffee shops and clothing stores that tend to be concentrated in certain neighborhoods where Somalis work, live and socialize.

At the same time, Somali-Americans have also found their way in local politics. In 2013, Minneapolis elected its first Somali-American City Council member, Abdi Warsame. The next year, Siad Ali was elected the Minneapolis school board; and last year, Ilhan Omar became the first Somali-American to be elected to a state Legislature.

Those two factors — the community’s entrepreneurship and growing political clout — has formed a major part of the narrative about Somali success, especially among those who compare Somalis in Minnesota to those in other parts of the world.

When officials from Sweden started visiting Minnesota, for example, they made a point of connecting with entrepreneurs to understand how they managed to establish their shops. One of the entrepreneurs they met was Kahin, the Afro Deli owner, who told the group that many in the community go into business trying to serve the Somali population in a place where it’s relatively easy to start a business, which isn’t the case in Sweden.

“This is a problem that we need to address in our government in order for the Somalis to have the freedom to establish businesses, like here,” Kurt Eliasson, an official from the Swedish Association of Public Housing, told me in 2012. “If this becomes possible, then they don’t have to be dependent on government assistance.”

Downplaying More Widespread Problems

Yusuf, the MPS teacher, said it’s understandable why many — including many Somali Americans in Minnesota — want to focus on the community’s economic contributions and political muscle. But he, like many others, takes issue with the fact that people are looking at the community’s “unique” experiences that highlight achievement while downplaying more widespread problems.

“Yes, there are some successful entrepreneurs,” Yusuf said. “Yes, there are some Somali elected officials. But there are also many living in poverty; there are people who are still dealing with language barriers.”

In fact, according to a 2016 report by the Minnesota State Demographic Center, most Somali-Americans remain at the lowest rung of the socioeconomic ladder. Nearly 57 percent of Somalis live in poverty, according to the report, while 26 percent live in near-poverty. Other measures also show how many Somali-Americans are struggling, even compared to other minority groups in the state. Somalis currently have the lowest median household income among immigrant and minority groups in Minnesota, as well as the lowest rates of educational attainment and home ownership.

In fact, according to a 2016 report by the Minnesota State Demographic Center, most Somali-Americans remain at the lowest rung of the socioeconomic ladder. Nearly 57 percent of Somalis live in poverty, according to the report, while 26 percent live in near-poverty. Other measures also show how many Somali-Americans are struggling, even compared to other minority groups in the state. Somalis currently have the lowest median household income among immigrant and minority groups in Minnesota, as well as the lowest rates of educational attainment and home ownership.

What’s more, even some of the signs of success can be misleading. Many of the community’s small business owners, especially those in Minneapolis malls, are struggling to keep their doors open, said Kahin. Most are owned and operated by elderly women who, because of their limited English proficiency, aren’t able to participate in the traditional labor market. “Almost all of the stores in these malls sell identical clothes,” Kahin said. “Many owners barely secure the monthly rent income of their shops, let alone making profits.”

Better Days Ahead

Ryan Allen, an immigration expert at the University of Minnesota, says the socioeconomic challenges that Somali-Americans face aren’t unique. In fact, they tend to mirror the experience of several groups, most notable Italian-Americans. “They were highly discriminated against because of their religion, and many people considered them to be a different race,” said Allen. “So they had to become entrepreneurs to survive economically.”

With time, the economic status of Italian immigrants improved as they gradually became more proficient in English and integrated into society — a pattern that he now sees in the Somali-American community.

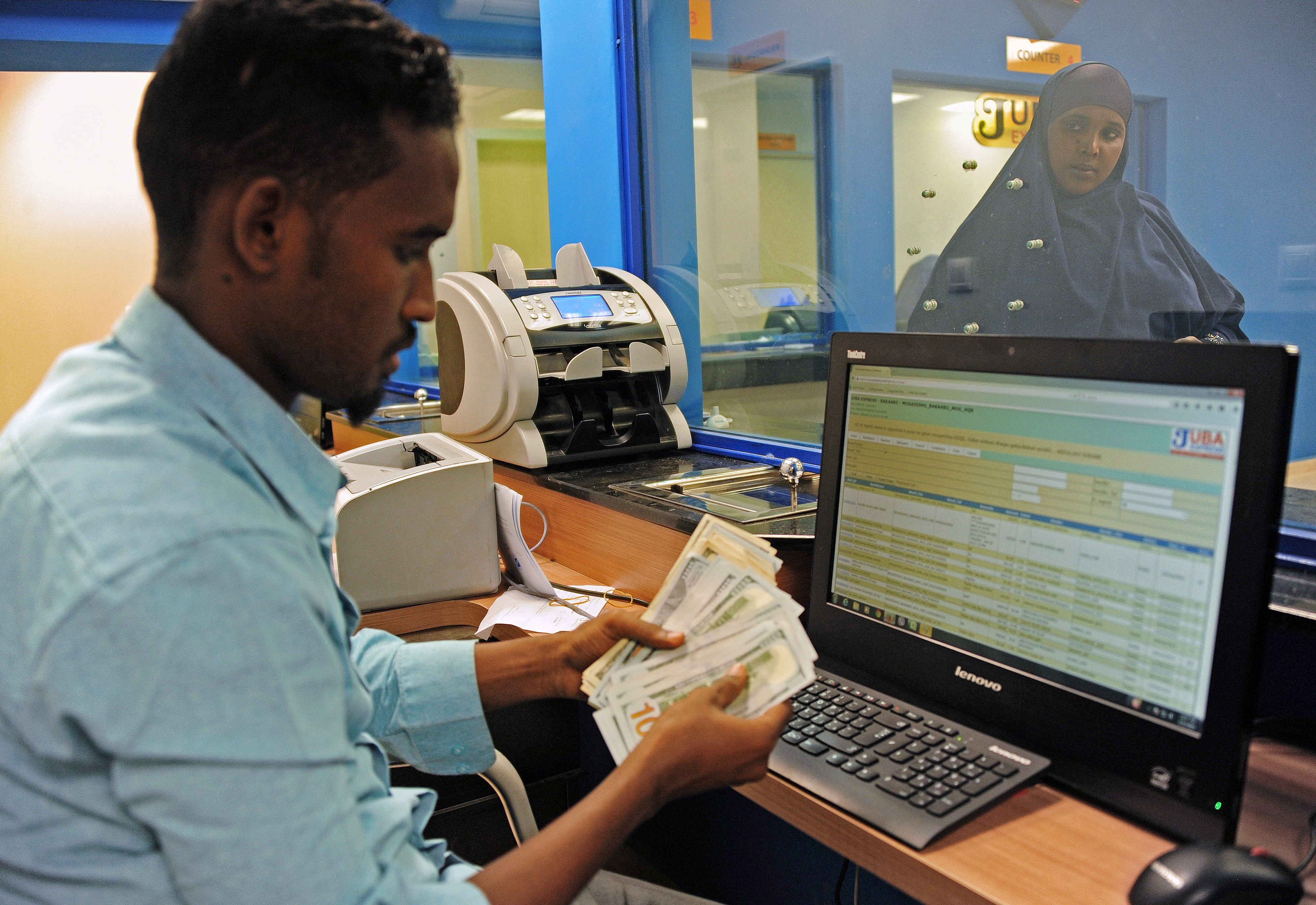

A customer (R) waits to collect money at the Juba Express money transfer company in Mogadishu on February 12, 2015. The US-based Merchants Bank of California has said it will halt its services to money transfer companies in Somalia, a decision aid groups say would stop up to 80 percent of the $200 million sent annually by relatives in the United States from reaching Somalia. With no formal banking system in the impoverished Horn of Africa nation, diaspora Somalis across the world turn to money transfer services to send money back home support their families, sending some $1.3 billion (1.1 billion euros) each year. Banks have become increasingly reluctant to keep them as customers as regulators crack down on money laundering and the funding of terrorism. Photo Credit: Mohamed Abdiwahab/AFP/Getty Images

Allen predicts that the second-generation of Somali immigrants, who, according to the Minnesota State Demographic Center, now make up nearly 40 percent of the community, can expect to do much better than their parents, both economically and socially. “The second generation of refugees have outcomes that look a whole like native-born children,” he says. “They go to college at the same rate and their economic outcomes look a lot like native-born children.”

It’s a sentiment Yusuf agrees with. He says that many second-generation Somalis in the Twin Cities metro area are serving as engineers, lawyers, doctors, accountants, educators, law-enforcement officers, artists, and designers. “They have assimilated into the mainstream America,” he says.

All that said, the backgrounds and experiences of Somali-Americans who immigrate to the U.S. can vary widely. And different people in the community have adjusted to life in Minnesota at different paces. Some, for example, have managed to quickly climb the rungs of the socioeconomic ladder; others are struggling to make ends meet.

Whatever the case, says Hamse Warfa, an author and entrepreneur, it’s important not to treat the community’s economic status as an intractable issue, but as a Minnesota problem that must be confronted.

“The Somali-American community is part of the future workforce of the state,” he says. “The implications of these high poverty rates will potentially create a barrier to the economic mobility of the state.”

Be the first to comment on "The Complicated Reality Behind the Story of the Somali Community’s Success in Minnesota"